Relationship Between Groundwater and Aquifers

Guest post by Christopher Roemmele, PhD

Water is essential for all living things. It continuously cycles through the atmosphere, over land, and through the ground. Groundwater is an important source of freshwater on Earth. It is also the primary water source for homes and neighborhoods that are not serviced by public water systems.

It is important for well owners to understand the characteristics of groundwater, how it relates to what is beneath the Earth’s surface, and how all of this impacts private wells. Here are some key concepts well owners should understand about groundwater and their wells.

Groundwater

Groundwater is the water that exists in the soil, rock, sediment, fractures and pore spaces beneath the Earth’s surface. Although groundwater occurs just about everywhere beneath the Earth’s surface, it is rarely deeper than one kilometer (0.62 miles) below the surface.

Groundwater is the water that exists in the soil, rock, sediment, fractures and pore spaces beneath the Earth’s surface. Although groundwater occurs just about everywhere beneath the Earth’s surface, it is rarely deeper than one kilometer (0.62 miles) below the surface.

If you could gather up all of Earth’s groundwater and put it on Earth’s surface, it would form a layer of water about 50 meters thick, which is the length of an Olympic sized swimming pool.

Because groundwater is largely hidden from view and is out of sight out of mind, it is often forgotten and subject to contamination and overuse.

Where does groundwater come from? The answer lies within the water cycle or hydraulic cycle (circulation of water in the Earth-atmosphere system). Groundwater originates as rain or snow. When it lands on the ground, the water moves through the soil and subsurface to become a part of the groundwater system. It eventually may make its way back to streams, lakes, or oceans.

Here is the general process:

- Water evaporates (changes from liquid to gas) from oceans and lakes and turns into water vapor

- As water vapor moves through the atmosphere, it may cool and condense into water (changes from gas to liquid) and ultimately forms clouds

- When there is sufficient water in a cloud, it falls as precipitation (rain, and when the cloud is cold, snow)

Because precipitation falls from clouds to Earth’s surface, there is runoff (water that flows over the surface in rills and gullies) and infiltration (downward percolation of water through the soil or sediment at the surface). Eventually, this infiltrating groundwater gets stored in pores (open spaces) within rocks, loose unconsolidated sediments, and soil close to Earth’s surface.

In fact, most of the groundwater accessed by humans through wells is within 100 meters (0.062 miles) of the Earth’s surface. The fact that rocks, sediment, and soil have open space is key to the study of and use of groundwater.

Porosity

A key property of rocks, sediment, and soil is porosity, which is the percentage of open space within sediment, soil, or rock. We might initially think porosity is just the space between the grains of sediment, soil, or a rock. Actually, measuring porosity can include the fractures that developed after the rock formed due to burial stresses, or in the case of some volcanic rocks, the holes that developed from the presence of gas in the magma or lava.

The porosity of a rock varies because of the size and shape of the grains in the rock. Another factor that affects the porosity of a rock is whether or not there is any material in the rock (or cement) to fill in the gaps between pore spaces and hold the grains together. If a rock has a lot of gaps between grains or crystals, then a lot of water can fit between the grains, and it will have a higher porosity.

A rock with good porosity can hold a lot of groundwater. Imagine a jar of pebbles – there is a good amount of empty space between all the pebbles. But if those spaces in the jar are filled in with smaller sediment like sand and silt, there is less pore space, and the porosity will go down.

Permeability

Permeability is another key property of rocks and sediments and soil, and it is closely related to porosity. Permeability measures how well-connected pore spaces are to one another, and the size of those connections. High permeability indicates that the pore spaces are well connected, and they allow groundwater to flow from one to another with some ease due to pressure and gravity, with less friction to slow the flow. Low permeability informs geologists that pore spaces are more isolated, and groundwater has limited means to get from one pore to another or does so very slowly.

Gravel and pebbles usually have higher permeability because the bigger pore spaces are well connected. With sediment like clay, most pore space is closed off, and groundwater does not move freely. A rock or sediment with high porosity does not necessarily mean that permeability will be high as well. However, low porosity is usually more indicative of low permeability.

Aquifer

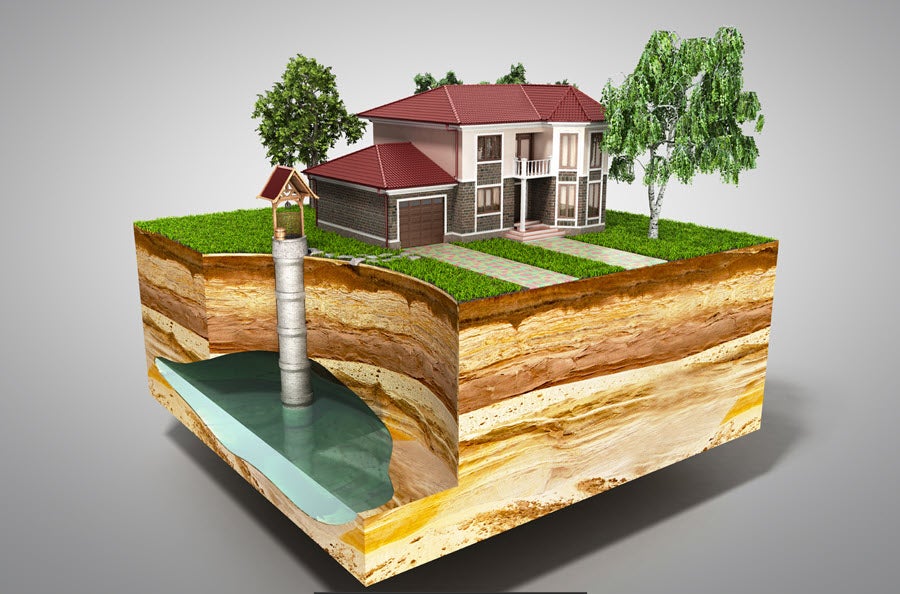

If you have a private well or need to dig a private well, you encounter the word “aquifer.” What are aquifers, and what do they have to do with groundwater and your well? Aquifers are large bodies and swaths of permeable material where groundwater is present and fills all the pore space.

As we outlined, groundwater is almost always present beneath our feet. As long as rock or sediment has a measurable porosity, there is likely to be groundwater. To access this water, you want to drill the well so that it penetrates a layer of rock or sediment where significant volumes of water can be extracted for use.

When you hire well drillers, make sure they drill down to rock or sediment with high permeability such as poorly cemented sandstone/sand, gravels, or highly fractured rock.

When they drill through the soil and rock and suddenly encounter groundwater, geologists call the top of the groundwater the water table. Every pore space below the water table should be filled with groundwater. Geologists call this the saturated zone.

Aquifers can be unconfined, where the water table is exposed to the Earth’s atmosphere in the uppermost surface/subsurface layer of rock/sediment/soil. Other aquifers are confined, which is when an aquifer is between layers of impermeable rock.

Aquitard

A geologist can also inform you if the rock or sediment the driller is in is an aquitard, which is a geological formation that restricts the flow of groundwater Aquitards have very low permeability – probably tightly packed clay and silt, cemented sandstones, or a solid, competent, non-fractured igneous or metamorphic rocks. And because porosity is low, permeability is too. Therefore, although there may be groundwater, it would not be worth the time or money to drill a well into this kind of material.

Christopher Roemmele, PhD., is Associate Professor and Assistant Chairperson of Earth and Space Sciences at West Chester University, PA

Key Terms

Groundwater: water that exists in the soil, rock, sediment, fractures and pore spaces beneath the Earth’s surface

Water Cycle: or hydrologic cycle, involves the continuous circulation of water in the Earth-atmosphere system.

Evaporation: change from liquid to gas

Condensation: change from gas to liquid

Precipitation: rain, snow, sleet, or hail that falls to or condenses on the ground

Runoff: water that flows over the surface in rills and gullies

Infiltration: downward percolation of water through the soil or sediment at the surface

Porosity: percentage of open space within sediment, soil, or rock

Permeability: measures how well-connected pore spaces are to one another and the size of those connections

Aquifer: are large bodies and swaths of porous and permeable material where groundwater is present and fills all the pore space

Water Table: top of groundwater

Saturated Zone: every pore space below the water table that is filled with groundwater

Aquitard: a geological formation that restricts the flow of groundwater

Aquagenx Well Water Test Kits

Buy on Amazon & Walmart

Buy kits that contain 2, 5, or 10 tests

Buy In Bulk from Aquagenx

Buy kits that contain 25, 50 or 100 tests